Evidence and Science-Based Approaches in Drug Policy – United Nations

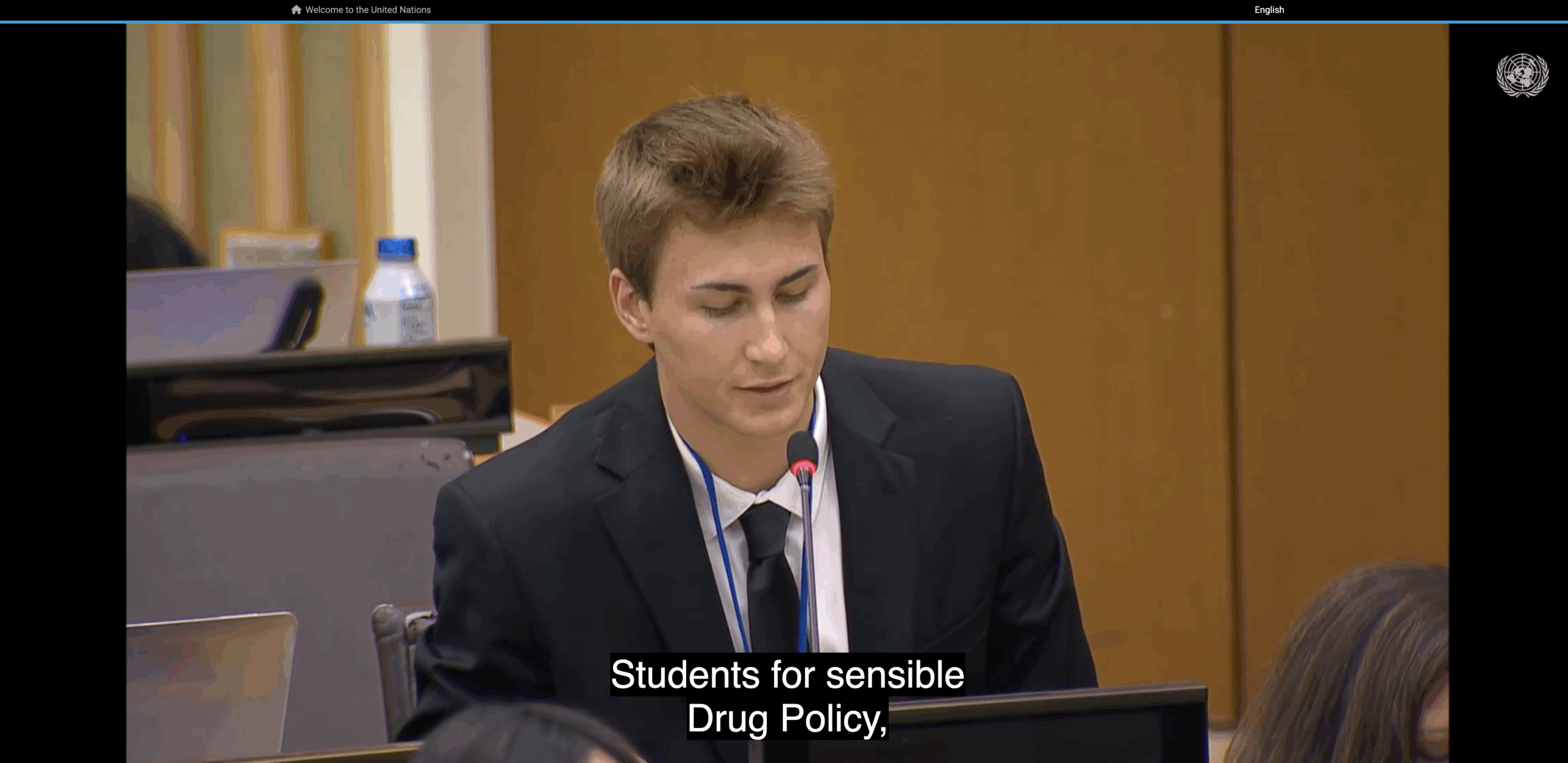

Written by Jackson Rund, Lake Superior State University SSDP

In July, I joined two fellow SSDP representatives, Zach Johnson from Fordham University and the New York Community Chapter, and Jorge Valderrabano from the New York Community Chapter at the United Nations Headquarters in New York City for the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF). Together, we formed part of SSDP’s delegation, working to bring drug policy into global development conversations that often leave it out entirely. Throughout the week, we connected with groups like the Major Group for Children and Youth (MGCY) and engaged in dialogues focused on shaping a more equitable and sustainable future.

The Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs, are a shared global roadmap designed to tackle poverty, improve health and education, reduce inequality, and address climate change by 2030. But it quickly became clear that drug policy reform remains one of the framework’s most overlooked issues. You can’t talk about SDG 3, which focuses on health and wellbeing, without acknowledging how prohibition blocks access to care, especially when 75 percent of mental health conditions in lower and middle-income countries go undetected. You can’t claim progress under SDG 9, which supports research and innovation, while outdated scheduling laws prevent scientists from studying the very substances that could advance treatment. This creates what SSDP has long described as “Research Harms.” And as for SDG 10, it’s impossible to talk about reducing inequality without naming the role criminalization plays in marginalizing entire communities.

During one of the sessions, I had the opportunity to share SSDP’s concerns. I spoke about the consequences of outdated scheduling systems and emphasized the need to treat medical cannabis as a basic public health right, particularly for patients with severe conditions like Dravet Syndrome.

“This isn’t just procedural,” I said. “It’s a structural failure that harms the most vulnerable.” I also posed a question that continues to stay with me: “What public health knowledge are we losing by locking substances out of the lab?”

Throughout the week, I joined conversations on health systems, harm reduction, intergenerational fairness, and youth participation. I heard from government leaders and civil society organizations working to build more inclusive, evidence-based public health approaches. Delegates spoke about the need for long-term planning that centers younger generations, and I saw moments of real honesty, like when the Swiss Secretary openly acknowledged that “a society free of drugs was a myth that caused more harm than good.” These discussions all pointed to the same truth: it’s time to move beyond well-meaning promises and start confronting the policies that are still costing lives.

One of the most important things I heard came from a delegate who reminded the room that sustainable development isn’t just about what we fund, it’s about what we’re willing to talk about. When drug policy is excluded from these global discussions, so are the people most harmed by it. That silence delays progress, and it’s something SSDP is working every day to change. From organizing panels at Psychedelic Science 2025 and the National Cannabis Festival to engaging at Cannabis Unity Week in DC and maintaining a voice at the United Nations, SSDP is keeping students and sensible reform at the heart of the conversation. Drug policy is not a side issue. It’s a core part of achieving health, equity, and justice on a global scale. And SSDP will continue showing up, speaking out, and driving that conversation forward.

Click here to watch Jorge’s address at HLPF.

Watch my segment on the UN’s website here.

My segment begins at the 1:08 mark of the session.